Defragmentation | 2024 – 2025 |

- Projects

- Paintings

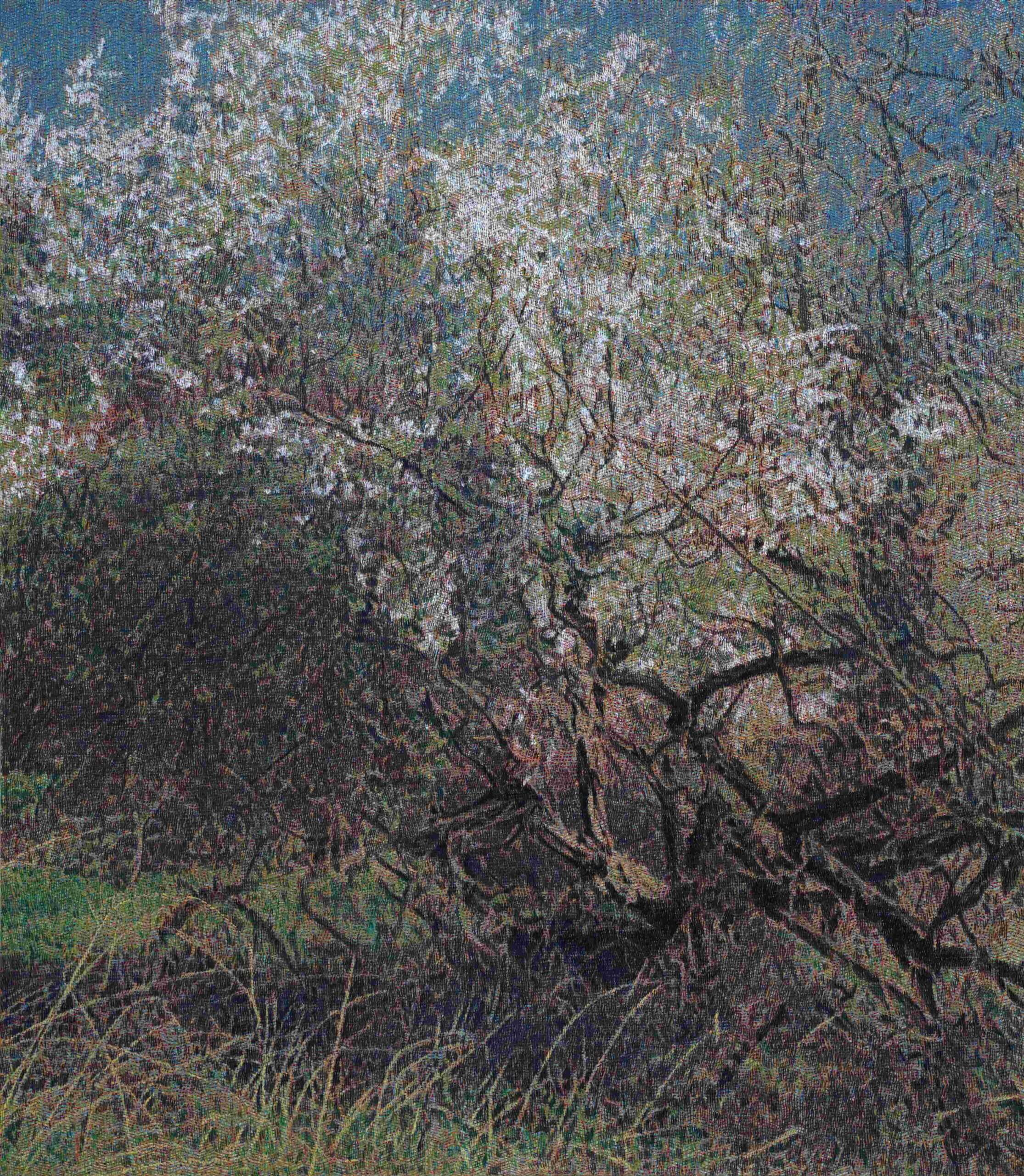

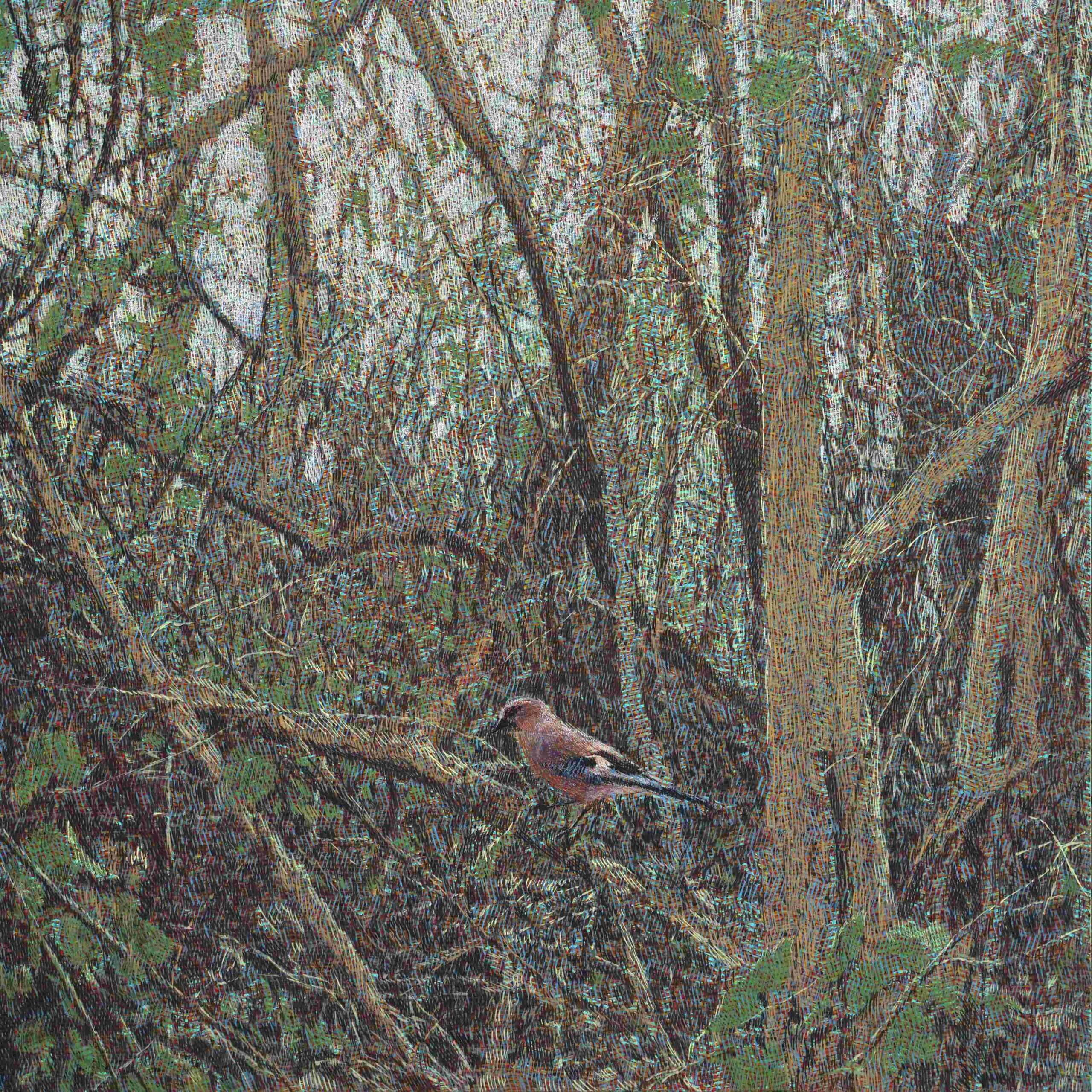

- Defragmentation | 2024 – 2025 |

- Topochronology I 2024- 2025 I

- Defragmentation | 2023 – 2004 |

- Violet Garden | 2020 | 2024

- Light-fields, Night-fields | 2019 – |

- Fragments | 2022- |

- Interfields | 2018 – 2022 |

- Triptychs | 2012-2018 |

- Blurred Fields, In the Middle of the Field | 2018 – 2019 |

- Equivalents | 2019 |

- Images of a Fading World | 2020 |

- Pinhole Project | 2021 |

- Other paintings | 2006-2018 |

- Prints

- Paintings

- Recent Activity

- Bio

exhibition Defragmentation at Aleš South Bohemian Gallery. 2025

curator: Dita Kozler

V kontextu environmentální estetiky může být nyní krajina vnímána jako mnohovrstevnatý kulturní konstrukt, prostor prožívání, interpretace a proměny. Krajina není jen fyzický prostor, scenérie nebo kulisa lidské existence, ale je také zrcadlem hodnot, vztahů a způsobů, jakými člověk vnímá své místo ve světě. I to, zda krajinu vnímáme jako krásnou či přirozenou, je podmíněno společenskými normami, vzděláním a osobní zkušeností. Estetik a environmentalista Karel Stibral zdůrazňuje, že „estetická zkušenost přírody není pouhým doplňkem poznání, ale přináší do vztahu člověka a přírody rozměr smyslu a hluboké citové angažovanosti.“[1] Hana Librová navíc upozorňuje na otázku odpovědnosti vůči krajině. Nejde jen o ochranu přírodních hodnot, ale i o péči o krajinu jako prostor významu, domova a kontinuity. Tato motivace však často koliduje s moderním životním stylem zaměřeným na výkon, spotřebu a mobilitu. V době klimatické krize a urbanizace se malovaná krajina stává místem zpomalení, obnovy a konfrontace s proměnlivým vztahem člověka k přírodě. Mnozí současní autoři navazují na dědictví romantismu či lyrického realismu, ale reinterpretují ho s vědomím ekologických nejistot a kulturní kritiky. Výrazný je posun od mimetického zobrazení ke zkoumání samotného fenoménu krajiny jako kulturní a environmentální konstrukce. Krajina se stává prostorem experimentu – kombinací gestické malby, konceptuálních přístupů a performativity. Z hlediska výtvarného umění tak krajina není jen vizuální motiv, ale symbol. Může vyjadřovat sounáležitost, ztrátu, kritiku i naději. V dialogu s krajinou se neodráží pouze estetická zkušenost či emoční prožitek, ale celý hodnotový rámec společnosti – její představy o přírodě, domově i budoucnosti.

[1] Karel Stibral, Estetika přírody: K historii estetického zhodnocení krajiny, Pavel Mervart 2019, s. 45

In the context of environmental aesthetics, landscape can now be perceived as a multi-layered cultural construct, a space for experience, interpretation and transformation. Landscape is not only a physical space, scenery or backdrop for human existence, but also a mirror of values, relationships and ways in which people perceive their place in the world. Even whether we perceive the landscape as beautiful or natural is conditioned by social norms, education and personal experience. Aesthetician and environmentalist Karel Stibral emphasises that “the aesthetic experience of nature is not merely a supplement to knowledge, but brings a dimension of meaning and deep emotional engagement to the relationship between humans and nature.”[1] Hana Librová also draws attention to the issue of responsibility towards the landscape. It is not only about protecting natural values, but also about caring for the landscape as a space of meaning, home and continuity. However, this motivation often conflicts with a modern lifestyle focused on performance, consumption and mobility. In times of climate crisis and urbanisation, the painted landscape becomes a place of slowing down, renewal and confrontation with the changing relationship between humans and nature. Many contemporary authors build on the legacy of Romanticism or lyrical realism, but reinterpret it with an awareness of ecological uncertainties and cultural criticism. There is a noticeable shift from mimetic representation to an exploration of the phenomenon of landscape itself as a cultural and environmental construct. Landscape becomes a space for experimentation – a combination of gestural painting, conceptual approaches and performativity. From the perspective of fine art, landscape is not just a visual motif but a symbol. It can express belonging, loss, criticism and hope. The dialogue with landscape reflects not only aesthetic or emotional experience, but the entire value framework of society – its ideas about nature, home and the future.

[1] Karel Stibral, Estetika přírody: K historii estetického zhodnocení krajiny, Pavel Mervart 2019, pg 45